I want to write about something that is often underappreciated and misunderstood, yet I think is very important: Resource Description Framework (RDF). RDF is especially important to know about if you are building a career in data-intensive applications. You will hear many things about RDF. It is a data model. It is a knowledge representation system. It is a data exchange format. It is knowledge graphs. It is a web standard. There is some truth to all of them.

My goal in this post is to tell you about RDF, its virtues, vices, history, and applications; at least as much as one can manage in a single blog post. I hope to clarify what RDF is, when you need it, and why I think it is a fundamental data model to know about. As I will highlight, RDF can even play an increasingly important role in the era of LLM-based applications. I will also discuss some fascinating topics in AI that intersect with databases: logic, reasoning, and knowledge representation systems. I also put in a minor plug at the end for a new feature we added called RDFGraphs, to import and query RDF data in Kuzu.

TL;DR: The key takeaways from this post are:

-

RDF overview: RDF is a simple and flexible data model, where both data and schema are simple sentences in the form of (subject, predicate/verb, object) triples. A collection of these triples forms a graph. RDF is further a knowledge representation system due to the standards around RDF, such as RDFS and OWL, that give clear meaning to certain vocabulary in triples, especially the verbs. This enables DBMSs1 to do automatic logical inference over triples. RDF has its historical roots in Semantic Web, which has its roots in good old-fashioned symbolic AI/knowledge representation and reasoning (KRR).

-

RDF virtues: The main pros of RDF are: (i) modeling complex, irregular domains; (ii) seamless schema and data querying; (iii) data integration without transformations; and (iv) automatic logical inference/reasoning.

-

RDF vices: The main cons of building large RDF databases are: (i) performance and scalability; (ii) verbosity; and (iii) inherent challenges of modeling complex domains, such as ensuring logical consistency in the database.

-

Role of RDF and reasoning in the context of LLMs: RDF and knowledge graphs are being used in retrieval augmented generation (RAG) to link the chunks or the entities in the chunks of text documents. Beyond RDF, for the role that advanced KRR systems can play in the era of LLMs, here is a great article by the late Douglas Lenat.

-

Kuzu RDFGraphs: RDFGraphs is a new feature in Kuzu to map RDF triples into Kuzu’s structured property graph model. This way you can query RDF datasets in Cypher, enhance them with property graph data, and benefit from Kuzu’s fast query processor.

RDF as a data model

Since the 1980s and possibly earlier, the database and AI communities have had different preferences

for referring to the information stored in information systems as “data” vs “knowledge”.2 Let’s put

this distinction aside for now. As a core database researcher, let me explain

RDF, first and foremost, as a data model. It is in fact an extremely simple and expressive

data model. For reasons I will explain below, it is considered a graph-based model.

To motivate RDF as a data model, let me start with a very obvious example where relational modeling will just not work. Let’s take the extremely ambitious goal of putting all of the knowledge on Wikipedia into structured, computer-processable records. This is the goal of projects/datasets like Wikidata, DBPedia, and Freebase which had gained immense popularity in 2010s when Google revealed that it used Freebase to return question answers as info-boxes. To appreciate how ambitious this goal is note that these projects aim to model all encyclopedic human knowledge as a database of records. But what would the tables be? Would you have a separate table for persons, institutions, locations, soccer clubs? Would you model the politicians in a table with their parties? But some politicians don’t have parties, and there are vastly different political roles out there. It is hopeless. You couldn’t even get started. The data is too irregular. It is too complex.

I did not have to go that extreme. Similar situations arise in many enterprises. As long as the modeled domain is large and complex enough, you will have trouble modeling the domain meaningfully as a set of tables. Think of cataloguing the products sold by an e-commerce company. Suppose your goal is to answer a variety of questions about the products for business reporting, analytics, and search purposes:

- How many products are there under the clothing category? How many are under the shirts category?

- Which products produced in Canada are subject to Textile Labeling Act?

- Which materials are used in Levi’s 511 jeans?

You need to model your products, their categories, the materials used in producing them, the regulations they are subject to, amongst other information. But your company (let’s call it “Global Corps”) sells tens of thousands of products from international merchants. The products under clothing will be very different from those in electronics or furniture. Regulations that apply to products will be vastly different across product categories and countries. Even within a single category, say “Jeans”, some products will be produced using two materials, others ten. The point is, the product catalogue of an e-commerce company can be very complex and irregular. If you want an enterprise-level database to answer such questions, you will have trouble coming up with a well-defined set of tables to give structure to this domain.

What you want is a more object-oriented model of the domain, one that allows putting entities under hierarchies of classes and categories, and having irregular sets of properties on entities and irregular relationships between entities. RDF, as a data model, is a great fit for modeling exactly such complex, irregular information. It is a great fit because it is a very simple model.

Virtue 1 and the basics of RDF: Flexible modeling

Before I start, let me point you to this book by Allemang and Hendler, Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist (see this more recent but paid edition). It is a great book to learn about RDF and its related standards that contains a ton of practical examples (which is the best way to understand technical material). The RDF data model consists of three main components:

- Resources: Resources model entities,

concepts, or even properties in the modeled domain. They are identified by unique internationalized resource identifiers (IRIs), which are URL-like

strings. IRIs are broadly in the form of <

prefix-namespace:local-identifier>. Some standard prefix names will be discussed later on. For our running example, let’s use the prefixhttp://global-corps.io/rdf-ex#for the namespace with abbreviationgc. The important thing is that resources model “things” in the domain and “things” can be both data and schema/meta-data. So entities in the domain are resources. For example, the IRIgc:Levis-511can model the jeans product Levi’s 511. At the same time, classes and types of entities are also resources. For example, IRIgc:Jeanscan model a class/type/category of jeans products (so it’s part of schema).3

-

Literals: Resources have properties which can be other resources or literals, which are values, such as strings or integers (explained momentarily).

-

Triples: Now we can describe how to express information in RDF. All information in RDF is expressed as a set of <subject, predicate, object> triples, which are short sentences. Subjects are resources, predicates are like verbs, and objects are either resources or literals. Here are some example triples about Global Corps’s product catalogue.

rdfandrdfsprefixes below are forhttp://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#andhttp://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#, which are namespace to identify several standardized RDF vocabulary (more on these standards later).

<gc:Levis-511, rdf:type, gc:LooseJeans>

<gc:Levis-511, gc:jean-size, 32>

<gc:Levis-511, gc:description, "Levi's standard slim fit jean made with denim.">

<gc:Mavi-Maxwell, rdf:type, gc:SlimJeans>

<gc:LooseJeans, rdf:subClassOf, gc:Jeans>

<gc:SlimJeans, rdf:subClassOf, gc:Jeans>

<gc:Jeans, rdf:subClassOf, gc:Clothing>

<gc:Clothing, rdf:subClassOf, gc:Product>

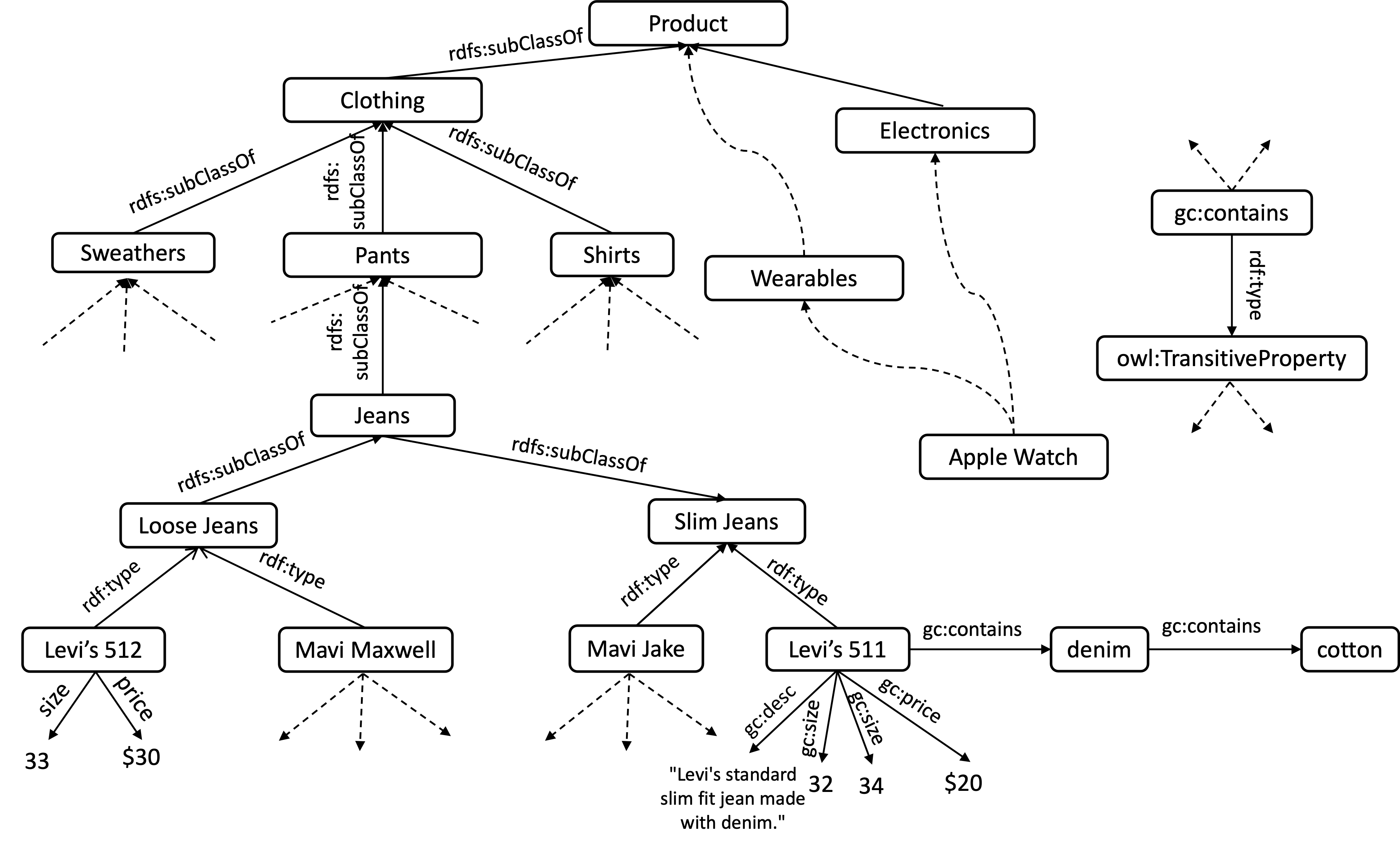

...The below image shows a sample of the database.

Triples are naturally modeled as edges between resources and literals.

This is why RDF is considered a graph-based data model. I’m removing

the IRIs of some resources and writing them in more natural terms, e.g., ‘Levi’s 511’ instead

of gc:Levis-511.

Some triples are between resources, such as <gc:Levis-511, rdf:type, gc:LooseJeans>,

while others are between a resource and literal, such as <gc:Levis-511, gc:jean-size, 32>.

Let me now highlight how expressive and flexible RDF is:

- Entities can be part of multiple classes. For example, the figure shows “Apple Watch” appearing

both under “Wearables” and “Electronics” through a chain of

rdf:typeandrdfs:subClassOfrelationships. - Entities can have irregular sets of properties. “Levi’s 511” has two sizes while

“Levi’s 512” has only one. “Levi’s 511” has four different properties,

gc:desc,gc:size, andgc:priceandgc:containswhile “Levi’s 512” has only two. - The predicates in the triples, which form the verbs, are themselves resources. So, we can express information

about the verbs of the sentences simply as additional triples.

For example,

gc:containsalso appears as a resource on the right side of the figure and is part of the <gc:contains,rdf:type,owl:TransitiveProperty> (more onowl:TransitivePropertylater).

That’s ample flexibility to model a complex domain. If there is new information you want to add to the database, as long as you have formed a consistent mental model of what things are and how to refer to them, you can add new triples to your database to represent it.

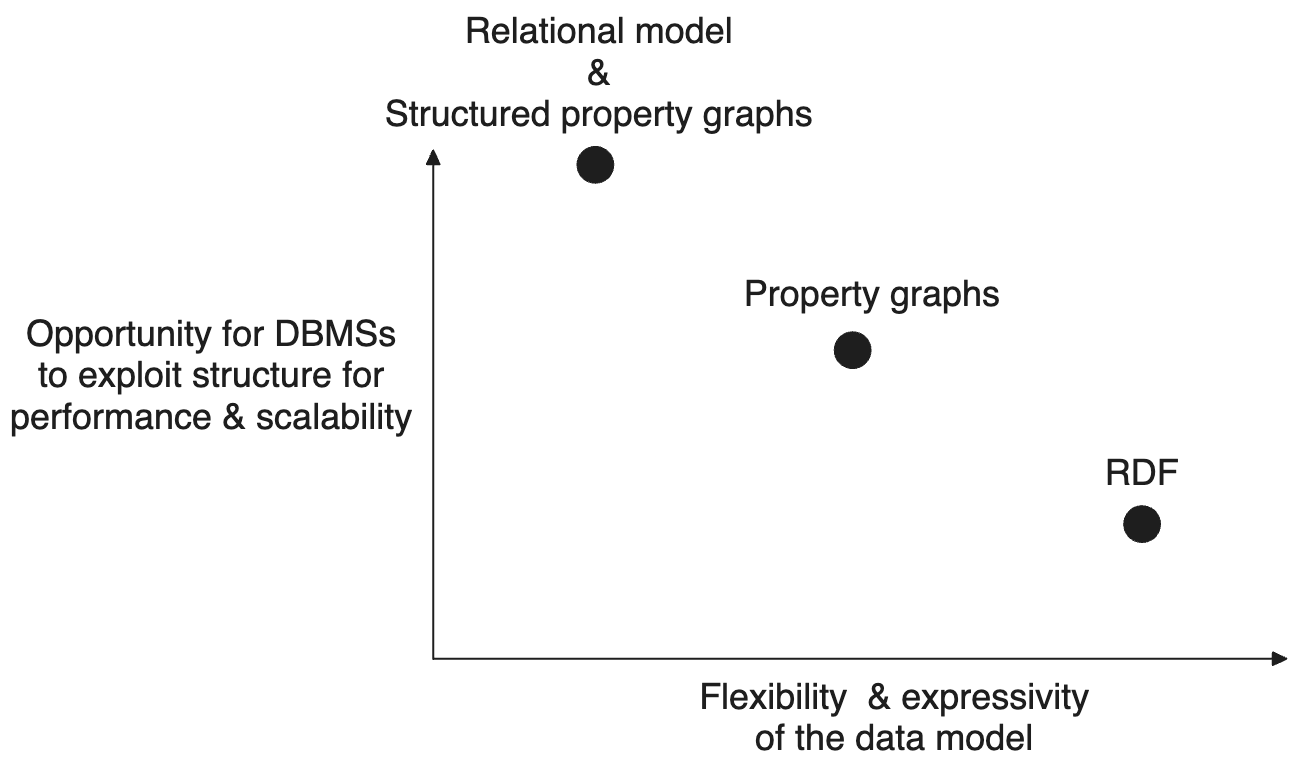

A rough view of data models

If you are eager to read about RDF as a knowledge representation system, you can skip to the next part. I want to describe a mental framework of data models that I find helpful when comparing them. Let’s focus on the relational model on the one side and the two popular graph-based data models, property graph (PG) and RDF on the other side. I am also adding Kuzu’s variant of the PG model, which we call the structured PG model, into this framework. The framework is shown in the figure below.

Think of the x-axis as representing the flexibility of the model to express complex domains (flexibility increases from left to right), and the y-axis as representing how much a DBMS can exploit in the structure to be fast and scalable at managing and querying databases in that model (see below for more). For simplicity, let’s ignore write performance.

-

Flexibility: The relational model is located as the left-most point because it is the most “rigid”, i.e., the most structured data model. RDF is the right-most point because it is the most flexible model. The original PG model introduced by Neo4j falls somewhere in between. On the one hand, PGs allow putting arbitrary key-value pairs on node and relationship records, so they provide more flexibility than the relational model. But in PG, you cannot construct proper type hierarchies as in RDF, nor can you model information about types of relationships as in RDF. RDF has a great foundation in knowledge representation and reasoning, so its expressiveness is very well thought out.

-

Opportunity for a DBMS to exploit structure for performance and scalability: It is impossible to predict the speed and scalability of systems just based on the data model they expose to users. The actual speed and scalability of a DBMS depends on many implementation choices the implementors make. However, as a rule of thumb, DBMSs can be faster and more scalable by exploiting structure in the data they manage. For example, DBMSs can compress and scan records fast if they are homogenous, e.g., if every item in “Jeans” has exactly one “size” property and “size” properties are all of the same type, e.g., integers. DBMSs can sort, join, and run fast aggregates on data if they know a priori how to get to each piece of data quickly, e.g., if they know their data type so they know the exact number of bytes used to store them on disk. If data is too complex and irregular, providing speed and scalability is harder for the DBMSs. This is a fundamental tradeoff in DBMSs. So, under that interpretation of the y-axis, the relational model would rank higher on the y-axis than RDF. We can debate whether there is enough structure in PGs to exploit for DBMSs. I don’t think so. Allowing arbitrary key-value properties and allowing nodes to have multiple labels makes the job of a PG DBMS harder. But I still put property graph model higher on the y-axis than RDF because in my experience most of the databases users put into PG DBMSs are extracted from relational systems so have inherent structure.

Note on Kuzu’s structured PG model: Kuzu implements a variant of the property graph data model that we call the structured property graph model. This is more or less equivalent to the relational model, except that we require users to identify their tables as “node” or “relationship” tables. That is why this model appears at the same location as the relational model in the figure above. This is a conscious choice that we are very happy about. We sacrifice some flexibility of the original PG model, e.g., nodes cannot have multiple labels in Kuzu. In return, we can exploit more structure in the data to do faster and more scalable query processing. Further, by requiring that tables are identified as nodes or relationships, we are able to provide a graph-based data model to users and implement Cypher, which has a very nice syntax for expressing paths and several common complex and recursive joins. In fact, I could put structured PG higher than the relational model in the figure because by identifying their tables as node vs relationship tables, users are telling us something important about their workloads. Specifically, they inform Kuzu that the relationship records will be used to join node records with their “neighbor” node records. This is true in other PG DBMSs as well. They also have the same information. Kuzu and other GDBMSs exploit this information by building join indices over the relationship tables, so that common joins of node records with their neighbors can be very fast.

RDF as a knowledge representation system

Let me now justify why some people refer to RDF as a knowledge representation system, or to RDF databases as knowledge graphs. Knowledge Representation and Reasoning (KRR) is one of the oldest branches of computer science and AI. Very broadly, KRR studies how to represent “knowledge” in computers, so we can develop intelligent systems that can efficiently reason, e.g., draw conclusions or generate new pieces of information from it. I will just leave a footnote about KRR here4 and the related field of the Semantic Web here5 because if I get into these topics, I just cannot get out. Plus, their foundations are all in logic, and in logic, things get very abstract very quickly, and we might soon find ourselves questioning whether a spoon we are looking at really exists. Let me just make the point of why RDF and its standards form a knowledge representation system.

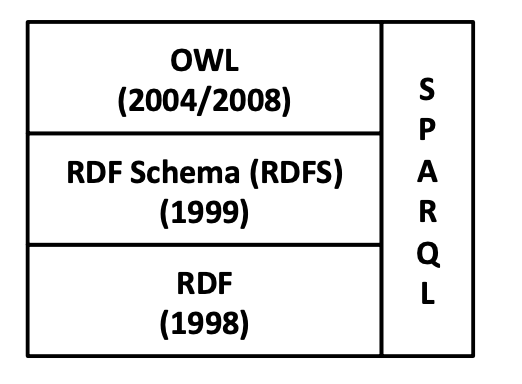

The figure above6 shows four of the important standards around RDF.

These come with a standard set of terms, such as rdf:type or rdfs:subClassOf,

that committees in the W3C standards community set down and gave specific

meaning to. Importantly, these terms are used in every RDF database out there, and if you use RDF, you will use them too.

This set of standardized terms and their precisely defined meanings allow systems to “reason” (see a few examples below). This is why RDF, along with

its standards, is called a knowledge representation system.

- RDF (standard, wiki) itself primarily enables modeling the data in your application

and a bit of schema with the

rdf:typeterm, putting your entities under categories. - RDFS (standard, wiki) and OWL (standard, wiki) primarily describe the schema, some reasoning/inference rules, and some constraints on the schema, i.e., the classes and properties of data.

- SPARQL (standard, wiki) is the query language to query RDF databases. As every other high-level query language, it is inspired by SQL but tailored for querying triples.

I will give one example here from an RDFS term rdfs:subClassOf to clarify what I mean when I say that RDFS and OWL

describe schema and enable reasoning.

In the example above we had a hierarchy of rdfs:subClassOf relationships between classes.

Let’s draw the triples as edges:

(gc:Levis-511)-[rdf:type]->(gc:LooseJeans)-[rdf:subClassOf]->(gc:Jeans)-[rdf:subClassOf]->(gc:Clothing)RDFS standard specifies (in formal logic-based notation)

that this implies, as expected, that gc:Levis-511 is a type of gc:Jeans (<gc:Levis-511, rdf:type, gc:Jeans>)

and also a type of gc:Clothing (<gc:Levis-511, rdf:type, gc:Clothing>).

In short, because the standards around RDF are formally defined to enable such reasoning, people refer to RDF and

its standards as a knowledge representation system. Indeed, some RDF DBMSs are able

to return those triples. Consider the following SPARQL query:

SELECT ?x WHERE {

gc:Levis-511 rdf:type ?x

}I hope the query is self-explanatory to anyone who knows SQL, asking for the

triples of the form <gc:Levis-511, rdf:type, ?x>. If you ask an RDF DBMS that implements the RDFS standard,

the query above will return three values for the unbound variable ?x:

gc:LooseJeans, gc:Jeans, and gc:Clothing. Note however that there are

no explicit triples in the system for <gc:Levis-511, rdf:type, gc:Jeans> and

<gc:Levis-511, rdf:type, gc:Clothing>. Those triples are automatically reasoned about, i.e., inferred.

Further RDF virtues

I discussed that one benefit of RDF is its flexibility in modeling complex domains. Let me now briefly describe a few other benefits you can get from RDF modeling.

Virtue 2: Schema-Data combined querying

Notice that in RDF there is no distinction between how information about data and schema are represented. Every statement is a triple and subjects of these triples can be resources/entities representing data, e.g., Levi’s 511, or classes, e.g., Jeans. Consider one of the motivating questions I had above:

Which products produced in Canada are subject to the Textile Labeling Act?

Suppose further that you have encoded which classes of items fall under Textile Labeling Act.

So maybe you had a triple <gc:Jeans, gc:subjectTo, gc:TextileLabelingAct>.

Note however, that this triple is not about the data. It’s about a class of items, so

it’s technically about the schema.

Now you can answer the question with the following query:

SELECT ?item WHERE {

?item rdf:type ?class .

?class gc:subjectTo gc:TextileLabelingAct .

}Again, an RDF system that implements reasoning, can, in our example, infer that Levi’s 511

is subject to Textile Labeling Act.

This might look like a simple feature at first, but it is not. Importantly, there is no obvious way

to do this in SQL. Ignoring the fact there is no automatic inference capability in RDBMSs,

you would have to put some records into a Jeans table, say with schema Jeans(name, price). Suppose

("Levi's 511", 20) is a record there. Then somehow you need to store the “metadata record” that table Jeans has the property

that it is subject to Textile Labeling Act. Then you need to join the records in the Jeans table with this metadata record.

But where will the metadata record be stored? Maybe we can put it in a table called Regulations(tableName, regulation) with

tuple ("Jeans", "Textile Labeling Act"). But then you couldn’t join this record with the ("Levi's 511", 20) record, since

they don’t contain any common values.

You would have to encode the table name of each tuple

with the tuple, so something like ("Levi's 511", 20, "Jeans") but you’re now going towards an RDF-like modeling approach.

In common-wisdom relational modeling, you don’t

unnecessarily repeat the table name “Jeans” with each tuple in the Jeans table. You can of

course do this in the relational model but your query will not be as simple as the one above. Most likely,

it will be a set of queries you have to run.

RDF, in contrast, is a very flexible model.

It’s closer to speaking a natural language. Every information is a sentence, so records can join

on schema names, or data values, or predicates/properties.

Virtue 3: Inference/reasoning

I already gave an example of inference that can be done through rdfs:subClassOf relationships above. Let me give

another example. You can define properties in RDF as transitive, symmetric, or reflexive. You use the

standardized OWL7 (which stands for “web ontology language”) vocabulary to do this. In our running example,

I did this with the gc:contains property, which was tagged with type owl:TransitiveProperty. This means

that if you have a triple <a, gc:contains, b> and <b, gc:contains, c>, then you can infer <a, gc:contains, c>.

So in a DBMS that implements the OWL standard for owl:TransitiveProperty, if you ask the query:

SELECT ?material WHERE {

gc:Levis-511 gc:contains ?material

}You could get both gc:denim and transitively gc:cotton, even though there is no direct <gc:Levis-511, gc:contains, gc:cotton> triple.

Virtue 4: Data integration

Another benefit of RDF is that the standardized RDF vocabulary can simplify data integration. I will give one example, and Allemang and Hendler’s book has many others. Suppose another department has created a new database about some products storing information about the merchants who sell them. Let’s suppose this database contains the following triples:

<md:Prod123, md:merchant, md:MerchantA>

<md:Prod123, md:merchant, md:MerchantB>

<md:MerchantA, md:locatedIn, md:Waterloo>

...The prefix namespace md stands for merchant data. Suppose md:Prod123

models Levi’s 511 in this database.

You can integrate this data with the database in the original running example by using

the standardized owl:sameAs predicate. So you can simply add the single <gc:Levis-511, owl:sameAs, md:Prod123>.

Then, suppose you ask the following query to a DBMS that implements the OWL standard:

SELECT ?merchant WHERE {

gc:Levis-511 md:merchant ?merchant

}You would get md:MerchantA and md:MerchantB as the merchants of gc:Levis-511.

No virtual schema designs or schema mappings are needed,

as one would have to do in a relational system. The query, above all, works

because: (i) RDF is very flexible and consists of simple sentences; and

(ii) standards around RDF are very clear about the meaning of owl:sameAs and its entailments.

You simply had to add a new sentence to your database, “Levi’s 511 and Prod123 are the same thing”,

and you have integrated your data correctly.

There are standardized vocabularies other than owl:sameAs to integrate data across databases.

For example, if in the original database you had a property gc:merchant with merchant information, you could

have also indicated <gc:merchant, owl:equivalentProperty, md:merchant>. Then you could query all merchants

of products either with gc:merchant or md:merchant property.

RDF vices: Performance, verbosity, inconsistencies

As I mentioned in my diagram of data models, as a rule of thumb, the more flexible a data model, the less structure there is to exploit, and so, the less performant and scalable you should expect a DBMS supporting the data model to be (in query performance at least). Again, I’m making a relative argument modulo the rest of the optimizations in the system. Lack of structure means that there are fewer optimizations a system can do.

The second obvious vice of RDF is that it can be verbose to model data. For example,

suppose you wanted to model that Levi’s 511, Levi’s 512, and Levi’s 513 are jeans and have sizes 32, 33, 34, respectively.

In relational modeling, you would have Jeans tables with 3 succinct tuples: ("Levis-511", 32), ("Levis-512", 33), ("Levis-513", 34).

In RDF, you have to work harder. You need to have 6 triples, 3 for types and 3 for size. For example two of the

triples for Levi’s 511 are

<gc:Levis-511, rdf:type, gc:LooseJeans>, <gc:Levis-511, gc:size, 32>. There is also additional verbosity

due to the use of IRIS to refer to resources,

which are long strings, even if their namespaces can be abbreviated. So expect this verbosity to slow your development down.

The third vice is that if you are in a situation when you need RDF, you are likely developing a database

that is modeling a complex domain. Therefore inherently, you will have to deal with a lot of challenges and pain of

modeling complex things. There are examples of large scale knowledge graph constructions that can take

many years of work. As an extreme example, the SNOMED project

aims to model all medical terms has required many decades of work.

One part of the problem is to keep your constraints, equivalences, and hierarchies consistent.

For example, you can indicate somewhere that <gc:Levis-511, owl:sameAs, md:Prod123>,

<gc:Prod123, owl:sameAs, xyz:Prod456> and somewhere else that <gc:Levis-511, owl:differentFrom, xyz:Prod456>.

Now your database is inconsistent.

It is unfair to say that this is a vice of RDF but be aware that if you are modeling a complex domain, with RDF or any

other approach, it is not going to be simple. By definition, you have embarked on a complex task.

But of course, no pain, no gain in life. If you invested and successfully modeled a complex domain in your enterprise, you can now use that data in several applications, perhaps most importantly in information retrieval and question answering (more on this momentarily).

Conclusions

My goal in this post was to tell you about RDF. What it is, what it is not, why I find it a very important data model to know about, and why I have a high opinion of it. If you were interested in RDF but never got deep into it, I hope I have piqued your interest to learn more. This post shouldn’t come across as me saying that RDF should be used for everything. On the contrary, what developers model and store in DBMSs often has perfect or close-to-perfect structure, and using either relational or property graph models would be the right modeling choice in those cases. But there are cases, as I outlined, where you need a model that’s more flexible and RDF is likely what you need.

I want to end with several notes.

A minor plug for Kuzu RDFGraphs

First, I want to highlight a new feature we introduced in Kuzu called RDFGraphs. Let me emphasize here that Kuzu’s native data model is not RDF — it is structured property graphs. But, part of our mission is to simplify graph modeling for people and the other part is to develop the most competent GDBMS out there in terms of performance and scalability, which we do by basing our core architecture on state-of-the-art data management principles. As part of the former goal, we want people to use Kuzu whenever they need to model their records as a graph, whether these records exist in CSV files, RDBMSs, or are already in an RDF triple format. In light of this, RDFGraphs is a lightweight extension of our structured property graph model that allows users to map RDF triples into a Kuzu database. Once your triples are in Kuzu, you can query them with Cypher (no inference of course), and further enhance them with other records you have modeled as a property graph. We also have some pre-loaded RDFGraphs you can download and start playing around with.

Remembering logic-based databases in the era of LLMs

RDF, knowledge graphs, and RAG in LLMs: Second, there might be an important role for RDF and knowledge graphs to play in the era of LLMs. People are actively working on doing better retrieval augmented generation (RAG) by extending LLMs with knowledge graphs. Some of these approaches try to retrieve data from an automatically generated triples from text. Others try to link the chunks in their documents by using a knowledge graph. I reviewed some of these approaches and my general opinions on this approach in a previous blog post on RAG.

Symbolic AI + LLM vision: RDF technology was popularized by the Semantic Web community and its roots go back to fundamental topics in AI on knowledge representation and reasoning. This is a fascinating area that is referred to as good old-fashioned (symbolic) AI, which may had its own winter for decades and been under the shadow of statistical AI for a while. However, symbolic AI is gaining more prominence lately in the context of LLMs, which are extremely popular and have severe reasoning limitations. In contrast to RAG, another direction to improve the output of LLMs is to combine them with systems that do reasoning, just like the simple inference examples I presented using RDF standards. For a good read on this vision of hybrid LLM + symbolic AI approach, I highly recommend this article co-authored by the late Douglas Lenat. Lenat is a legendary AI researcher who devoted his life to develop probably the most ambitious known symbolic AI system called Cyc. Cyc is a system that has common sense knowledge about the world based on millions of rules, such as “no person can be at more than one place at the same time”, or that “people believe that cats can breathe”. See this Lex Friedman podcast of Lenat to learn more and be fascinated by Cyc. In their article Lenat and his co-author Gary Marcus discuss a more direct approach than RAG where a knowledge base’s8 reasoning capabilities can help LLMs. Specifically, they describe five different opportunities through which LLMs can benefit from a symbolic AI that reasons using a knowledge graph/base. For example, it can double check if the LLM’s arguments are logically consistent (their first opportunity). Or when an LLM generates a conclusion (without argument), the symbolic reasoning AI can check if there is a sequence of inferences one can make to arrive at the same result (their fifth opportunity). Pursuing these visions would be very exciting.

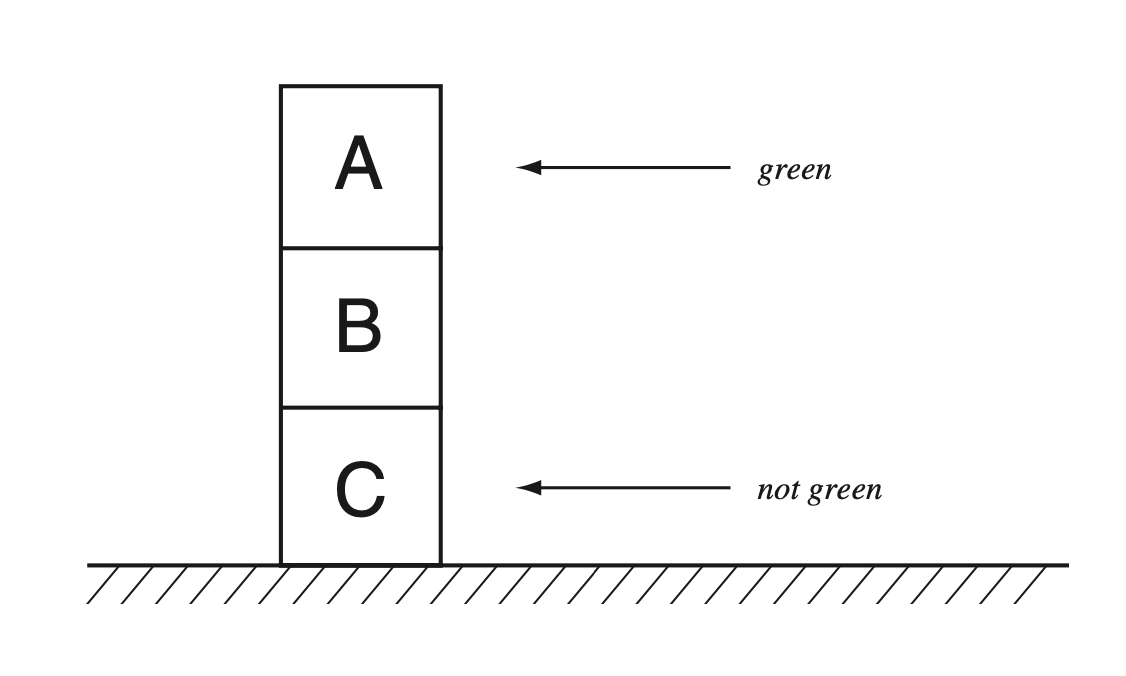

Remembering deductive databases: Database people generally love building systems that are scalable and fast, but dumb. RDF DBMSs or the logic-based deductive databases of 90s are relatively harder to scale and make performant. It has always surprised me that the database community never built and commercialized RDF DBMSs, with the exception of a few academic projects in early 2000s, e.g., RDF3X. Instead, serious RDF DBMSs have tended to be built by people from the Semantic Web community. But given the increased interest in symbolic AI, this has become a relevant topic again. To demonstrate what is possible in a system that can reason, consider the figure below copy-pasted from the Brachman and Levesque book on KRRs (Figure 2.1 there):

Suppose we model the boxes as tuples, and we are able to express that

each box has one color (which can be done in OWL with owl:cardinality)

and that has to be “green” or “not green”. Suppose we know that

the top box A is green and bottom box C is not green and the color of

box B is not known. We also want to model that A is on top B and B is on top of C.

Suppose we model these facts as triples using some IRIs to model the boxes

and xyz:color, xyz:onTopOf and owl:cardinality predicates.

Suppose we want to ask the following question: “are there (or how many)

green boxes are above not green boxes”. We could do this in SPARQL as follows:

SELECT count(*) WHERE {

?box1 xyz:color "green" .

?box1 xyz:ontopOf ?box2 .

?box2 xyz:color "not green" .

}No system that I know of can evaluate this query to return the correct answer,

which is 1. The reasoning is simple: the middle box B can either be green or not green.

If it is green, then (box1=B, box2=C) would match the pattern. If it is not green,

then (box1=A, box2=B) would match the pattern. I don’t think OWL-based reasoning

allows this (though don’t quote me on this). Who knows, maybe Cyc could do this.

An old ideal in computer science, primarily

in AI, but also in databases, such as in the context of deductive databases

of the 80s and 90s, was to develop systems that had such reasoning capabilities (though

not at the level in this example).9

Given the prominence of AI during these years and the need to

enhance the reasoning capabilities of existing LLM- and statistics-based AI,

it seems like a good time to revisit this ideal,

and rethink what deductive databases might look like in 2020s. This is yet another

reason to be interested in RDF, semantic web, and the broader field of KRR.

Phew! I covered a lot of content, and I may have raised more questions than I answered. But I hope I at least succeeded in giving you an overview and appreciation of RDF, and when and how to use it. I need an appropriate sentence to end the post, so let it be the following:

Long live the ideal of reasoning systems!

Footnotes

-

Several terms are used for systems that manage RDF and provide a high-level query language over them. These include RDF databases, RDF engines, triple stores, or RDF DBMSs. I will use “RDF DBMSs” in this post. ↩

-

Here is a fun quote on the distinction between “data” and “knowledge” from Jeff Ullman’s 1989 book “Principles of Database and Knowledge-Base Systems”: When referring to systems that implement logic-based query languages, Ullman writes (emphasis mine): “It has become fashionable to refer to the statements of these more expressive languages as “knowledge”, a term I abhor but find myself incapable of avoiding.” Ullman is well-known for his work on Datalog and logic-based databases, an area of databases that closely intersects with AI. ↩

-

As a side note, although I won’t use the term in this post, the set of resources that describe the schema/metadata of database, i.e., the classes and class hierarchies and the triples between them, are called ontologies. The rest of the resources represent data. ↩

-

To learn more about KRR, I highly recommend this well-written and accessible book by Brachman and Levesque, Knowledge Representation and Reasoning. I am not particularly recommending that you read this if you are interested in learning about RDF and how to use it. This is more a book for graduate seminars covering the foundations of the topic, but it is a very good read. KRR systems often use logic-based languages to represent knowledge. Often these languages are subsets of first order logic (FOL), where information is represented as formulas like . If you want to indulge yourself in science and ponder about why we cannot compute whether a query/formula in FOL is true or false (results from Gödel, Church, and Turing in 1930s) and why some subsets of FOL called Description Logics are always computable, read the Brachman and Levesque book and this Handbook on Description Logics. ↩

-

RDF apparently first emerged as a way to label resources on the web mid 1990s. It was later popularized by the Semantic Web community starting in the 2000s. This is a separate community of its own that intersects with the AI, especially the KRR, community. Historically, the Semantic Web community aims to make the web more intelligent by describing the “semantics/meaning” of the pages and general content on the web. Here is the seminal paper called “The Semantic Web” by Berners-Lee, Hendler (same Hendler above), and Lassila that got the field going. The vision has been to have an alternative web for computers that can automatically understand what is on the web. The vision imagines websites describing the meaning of their contents in some structured or semi-structured form, such as RDF triples. This vision has not been realized as originally described in the paper, but the technologies and standards developed by the Semantic Web community, such as RDF, RDFS, OWL, and SPARQL have seen adoption. ↩

-

The image is a copy of Figure 1 from Juan Sequeda’s PhD thesis ↩

-

Kudos to the standardizing committee for taking the liberty to define an abbreviation that does not follow the order of the words. The typical abbreviation for “web ontology language” would be WOL, something significantly less catchy than OWL. ↩

-

In Lenat’s terminology, knowledge bases are more expressive than the knowledge graphs I described here. What I showed you might look quite expressive but as I mentioned in a previous footnote, RDF standards are limited subsets of first-order logic called Description Logics, so they cannot express a lot of constraints and rules. Cyc, as Lenat describes in his article, is based on a language called CycL, that covers the full spectrum of first-order logic. ↩

-

I should note that deductive databases were not as ambitious in terms of their reasoning capabilities as the work that came out of KRR and Semantic Web communities. Deductive databases were primarily focused on laying the foundations of Datalog DBMSs, which are great at expressing views and recursive computations declaratively, but still do not have means to express the constraints of RDFS or OWL, so they could not solve the 3 boxes example above automatically. ↩